Day Five of my ten-minute short story challenge! I missed Day Four yesterday, but we carry on. Read Monday's entry here, Tuesday's entry here, and Wednesday's entry here.

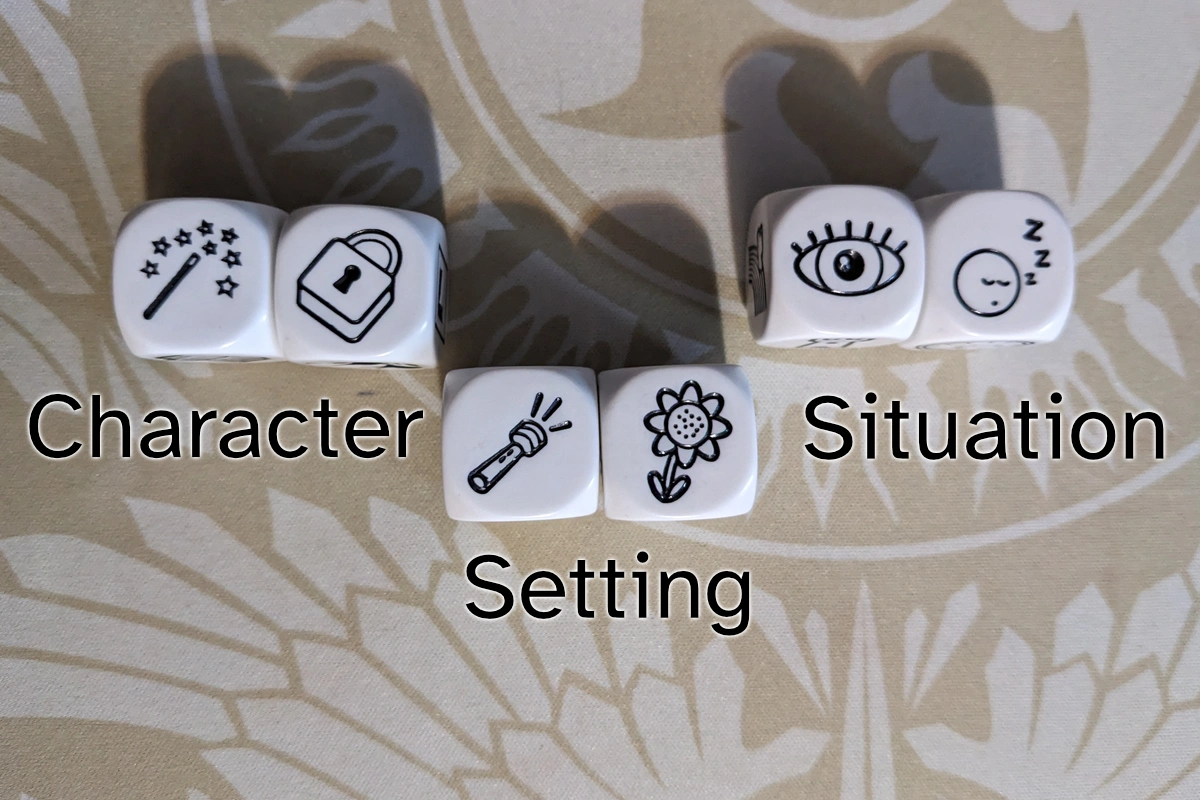

I interpreted the character to be someone who could magically open locks, the setting to be a greenhouse, and the situation to be a sleeping guardian waking up.

Because I've got magic hands, they call me Magic Hans. Now, sane and rational people know that magic doesn't exist, so it's just a joke.

I've really, truly got magic hands, though. I can open any lock just by poking and prodding at it for a few moments. Padlock, keypad, even a laptop password—if it was meant to keep me out, I can get it without a problem.

I work for some shady people who deal in high-tech secrets. I'm grateful for the work. They pay real well. I'm also paranoid that they'll sell me to the highest bidder if they realize my full capabilities, so I employ a little misdirection. I carry the most expensive lockpicks on the black market and a little electronic box with a half-dozen cables poking out of it which really connect to nothing at all—but as far as my confederates know, it's how I crack every security alarm and computer server we need to get into. I'm real careful about seeming secretive about my "tools." The only problem is at least one or two other guys clearly want to make off with my little cable box, and if they do, and they find it's empty, then the real questions will start.

Don't ask where the magic came from. I was born with it, as far as I know.

Tonight, that magic will come in very handy. We've crawled under the city's old maintaince tunnels, sloshing through the blackish sludge remnants of decomposed clones banished down into the dark. The soupy stuff, believe it or not, carries no scent at all. But it's apparently miraculous fertilizer if you mix it with some very smelly chemicals. That's, supposedly, what our mark's been doing.

Borble's his name. He's got a farm of sorts down here, in one of the ancient supply houses that used to service the clone workers who built the city in the first place. Nobody comes down here anymore on account of the whole business with the nervous systems of those clones surviving and... adapting.

We lured them away with bait an hour ago. They won't be bothering us until Jimnothy's nothing but a skeleton.

Poor Jimnothy.

The heavy riveted door's before us, set into the old brick walls. There's a security box jutting from the brick beside the door. It's been slathered with black paint and sludge in an attempt to make it look like part of the original construction.

I know better.

I put my hand to the metal, the slime squelching beneath my magic fingers.